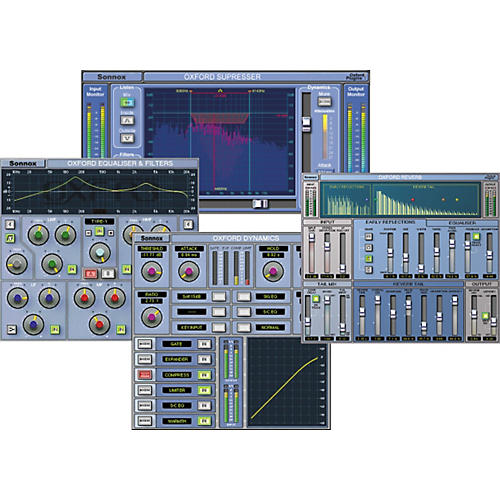

Plug Ins Effects Tdm

Space is the ultimate reverb plugin for music and post-production applications. From the largest concert hall to the densest plate reverb, Space delivers the pristine sound of natural reverb spaces with the familiar controls used in high-end hardware reverb units. By combining the sampled acoustics of real reverb spaces with advanced DSP. Further than Reverb One, available in AAX DSP/ Native and Tdm plugin formats. Add effects quickly and easily through the extensive library of reverb presets.

Audio Plug-ins- -VST (Virtual Studio Technology) is a real-time native plug-in formatcreated by Steinberg. Currently there are over 300 plug-ins made forVST. It is becoming one of the most widely-used formats for audioplug-ins. VST plug-ins differ from Direct X plug-ins in a few areas:VST can be used on PC's or Mac's, it is dependent on the hostprogram.AU -Audio Units is the plug-in format developed by Apple to coincidewith their new audio and MIDI technologies in OS X. Certain programslike Logic support Audio units exclusively, while other programs likeDigital Performer 4 support their own MAS format as well as AudioUnits.

Audio Units are handled at the level of the OS X operating sytemitself and for programmers they can have a certain advantages in thattwo seperate engines exist for the GUI of the plug-in as well as thesound engine itself, allowing for a more advance user interfacedesign.Direct X Plug-Ins Direct X is a real-time plug-in (i.e., Direct Xplug-ins can process or alter the sound without creating a new file).Direct X uses 'native processing' to function. Native processing usesthe existing power of your CPU to process audio. Native processing hasbecome more popular as CPU's keep getting faster. Direct X was createdby Microsoft for Windows users to play fast video games without usingDOS. Microsoft saw an opportunity to unify the gaming industry, theirresult was Direct X. Direct X uses low level application programminginterfaces (API's) for high performance multimedia applications such asplug-ins. It includes support for sound, music, graphics and networkapplications.

Host programs must implement Direct X to runplug-ins.RTAS (Real Time Audio Suite) is a new plug-in format created byDigidesign for Pro Tools LE. RTAS is the next generation of AudioSuiteplug-ins. RTAS uses host based processing, your CPU, to run. RTAS isonly limited by the available CPU processing power. RTAS offers similarperformance to TDM in that each plug-in is fully automatable.TDM (Time Domain Multiplex) is a plug-in format created by Digidesignfor Pro Tools systems. TDM can only function with Digidesign Farmcards.

The number of plug-ins that you use depends on how many Farmcards you have and the type of plug-in. TDM is a 24 bit, 256 channelpath that integrates mixing and real time digital signal processing.This plug-in format offers zero latency and is fully automatable.HTDM stands for 'Host TDM' and refers to Plug-Ins that do all audioprocessing on the host CPU instead of the DSP chips found on your TDMhardware. They use a single, shared DSP on the TDM system to allow theaudio from these host Plug-In processes to stream in or out of thesystem. The faster your computer, the more Plug-Ins you will be able torun.

HTDM Plug-Ins allow the power and flexibility of host-basedprocessing for synths and sampling to directly integrate into ProTools. You can work with these Plug-Ins as you would use standard TDMPlug-Ins, including major benefits like using Pro Tools automation (inaddition to MIDI) to automate parameters, or using control surfaces forhands-on control of Plug-In parameters.AAX (Avid AudioeXtension) is Avid’s new advanced plug-in format, offeringworkflows and sound parity when sharing sessions betweenDSP-accelerated and native-based Pro Tools systems. The formatcomes in two flavors: AAX DSP—compatible with Pro Tools HDXsystems only (TDM is not supported in Pro Tools HDX) AAXNative—compatible with any system running Pro Tools/Pro ToolsHD 10 softwareMAS (MOTU Audio System) is a real-time native plug-in format created byMark of the Unicorn. MAS was created as a proprietary plug-in formatfor Performer and Digital Performer. MAS plug-ins are fully automatableand do not require external DSP. MAS is becoming a widely supportedformat by third party developers and currently supports a wide range ofsoftware synthesizers.

Available on Macintosh OS systems that use MAS.Host programs must implement MAS to run plug-ins.The Powercore format is a hardware-supported plugin that can be used inVST and Audio Unit compatible applications. Hardware supported pluginsrequire the hardware be present to run. They also take strain off theCPU by doing the processing in hardware, hence there is less of a drainon the computer for processing audio in real time. Future development of thePowerCore platform has been ceased. As part of a largerstrategic review, they have decided to cease furtherdevelopment of the PowerCore product range, including hardwareunits as well as software for the PowerCore platform. With themost recent release of software version 4.0, PowerCore isfully compatible with current operating systems, such as MacOS X Leopard, Mac OS X Snow Leopard, Windows XP, Windows Vistaand Windows 7, as well as the most popular DAWs – 32 bit and64 bit.LADSPA is an acronym for Linux Audio Developers Simple PluginAPI. It is a standard for handling filters and effects,licensed under the GNU LGPL.

It was originally designed forLinux through consensus on the Linux Audio Developers MailingList, but works on a variety of other platforms. It is used inmany free audio software projects and there is a wide range ofLADSPA plugins available.LV2 (LADSPA version 2) is an open standard for plugins andmatching host applications, mainly targeted at audioprocessing and generation. LV2 is a simple but extensiblesuccessor of LADSPA, intended to address the limitations ofLADSPA which many applications have outgrown.Currently there is support for LV2 in Ardour, Qtractor,Traverso DAW, and the Linux version of Audacity.

LV2 replacesthe former DSSI plugin infrastructure.DSSI stands for Disposable Soft Synth Interface. It is avirtual instrument (software synthesizer) plugin architecturefor use by music sequencer applications. It was designed forapplications running under Linux, although there is nothingspecific to Linux in the interface itself.

Chinese (Traditional and Simplified), English, French, German, Japanese, Korean, SpanishWebsitePro Tools is a developed and released by (formerly ) for and used for music creation and production, sound for picture (, audio and ) and, more generally, editing and processes.Pro Tools can run as standalone or operate using a range of external and internal with on-board (DSP), used to provide additional processing power to the host computer to process real-time —such as, and — and to obtain lower audio performance. Like all digital audio workstation software, Pro Tools can perform the functions of a and a along with additional features that can only be performed in the digital domain, such as and editing—most of audio handling is done without overwriting the source files—, track compositing with multiple playlists, and faster-than-realtime mixdown.Audio, and video tracks are graphically represented in a timeline., and hardware emulators—such as or guitar amplifiers—can be added, adjusted and processed in real-time in a.

16-bit, 24-bit, and audio at up to 192 kHz are supported. Pro Tools supports mixed bit depths and audio formats in a session: , and (SD2 format was dropped with Pro Tools 10). It also imports and exports in the formats, and imports audio from video files.

It has also incorporated video editing capabilities, so users can import and manipulate high definition video file formats such as XDCAM, MJPG-A, PhotoJPG, DV25, and more. It features, tempo maps, elastic audio and; supports mixing in, and sound using.The Pro Tools mix engine, supported until 2011 with version 10, employed for plug-in processing and for mixing. Current HDX hardware systems, HD Native and native systems use resolution for plug-ins and floating point summing; the software and the audio engine were adapted to from version 11. The timeline of Pro Tools 9 showing audio and MIDI tracks, running onWorkflow in Pro Tools is organized into two main windows: the timeline is shown in the Edit window, while the mixer is shown in the Mix window. MIDI and Score Editor windows provide a dedicated environment to edit MIDI. Different window layouts, along with shown and hidden tracks and their width settings, can be stored and recalled from the Window configuration list.

Timeline The timeline provides a graphical representation of all types of tracks: the audio or (when zoomed in) for audio tracks, a showing MIDI notes and controller values for MIDI and Instrument tracks, a sequence of frame thumbnails for video tracks, audio levels for auxiliary, master and master tracks. Alternate audio and MIDI content can be recorded, shown and edited in multiple layers for each track (called playlists), which can be used for track compositing.

All the mixer parameters (such as track and sends volume, pan and mute status) and plug-in parameters can be changed over time through. Any automation type can be shown and edited in multiple lanes for each track.

Track-based volume automation can be converted to clip-based automation and vice versa; automation of any type can also be copied and pasted to any other automation type.Tempo and meter changes can be programmed on the timeline; both MIDI and audio clips can move or time-stretch to follow tempo changes ('tick-based' tracks) or maintain their absolute position ('sample-based' tracks). Elastic Audio must be enabled in order to allow time stretching of audio clips. Editing Audio and MIDI clips can be moved, cut and duplicated non-destructively on the timeline (edits change the clip organization on the timeline, but source files are not overwritten). (TCE), equalization and dynamics processing can be applied to audio clips non-destructively and in real-time with Elastic Audio and Clip Effects; gain can be adjusted statically or dynamically on individual clips with Clip Gain; fade and crossfades can be applied, adjusted and are processed in real time. All other type of audio processing can be rendered on the timeline with the AudioSuite (non-real-time) version of AAX plug-ins.MIDI notes, velocities and controllers can be edited directly on the timeline, each MIDI track showing an individual piano roll, or in a specific window, where several MIDI and Instrument tracks can be shown together in a single piano roll with color-coding.

Multiple MIDI controllers for each track can be viewed and edited on different lanes. MIDI tracks can also be shown in within a score editor. MIDI data such as note quantization, duration, transposition, delay and velocity can also be altered non-destructively and in real-time on a track-per-track basis.Video files can be imported to one or more video tracks and organized in multiple playlists. Multiple video files can be edited together and played back in real-time. Video processing is GPU-accelerated and managed by the Avid Video Engine (AVE). Video output from one video track at once is provided in a separate window or can be viewed full-screen.

Mixing The virtual mixer shows controls and components of all tracks, including, input and output, automation read/write controls, buttons, arm record buttons, the, the and the track name. It also can show additional controls for the inserted, mic preamp gain, HEAT settings, and the EQ curve for each track.

Each track inputs and outputs can have different channel depths:, (LCR, 6.0/6.1, ); and formats are also available for mixing.Audio can be routed to and from different outputs and inputs, both physical and internal. Internal routing is achieved using busses and auxiliary tracks; each track can have multiple output assignments. Virtual instruments are loaded on Instrument tracks—a specific type of track which receives MIDI data in input and returns audio in output.Plug-ins are processed in real-time with dedicated DSP chips (AAX DSP format) or using the host computer's CPU (AAX Native format). Track rendering Audio, auxiliary and Instrument tracks (or MIDI tracks routed to a plug-in) can be committed to new tracks containing their rendered output. Virtual instruments can be committed to audio to prepare an arrangement project for mixing; track commit is also used to free up system resources during mixing, or when the session is shared with systems not having some plug-ins installed. Multiple tracks can be rendered at a time; it is also possible to render a specific timeline selection and define which range of inserts to render.Similarly, tracks can be frozen with their output rendered at the end of the plug-in chain or at a specific insert of their chain. Editing is suspended on frozen tracks, but they can be subsequently unfrozen if further adjustments are needed.

For example, virtual instruments can be frozen to free up system memory and improve performance, while keeping the possibility to unfreeze them to make changes to the arrangement. Mixdown The main mix of the session—or any internal mix bus or output path—can be bounced to disk in real-time (if hardware inserts from analog hardware are used, or if any audio or MIDI source is monitored live into the session) or offline (faster-than-realtime). The selected source can be mixed to mono, stereo or any other multichannel format. Multichannel mixdowns can be written as an interleaved audio file or in multiple mono files.

Multiple sources can also mixed down simultaneously—for example, to deliver.Audio and video can be bounced together to a QuickTime movie file. Session data exchange Session data can be partially or entirely exchanged with other DAWs or video editing software that support,. AAF and OMF sequences embed audio and video files with their metadata; when opened by the destination application, session structure is rebuilt with the original clip placement, edits and basic track and clip automation.Track contents and any of its properties can be selectively exchanged between Pro Tools sessions with Import Session Data (for example, importing audio clips from an external session to a designated track while keeping track settings, or importing track inserts while keeping audio clips). Similarly, the same track data for any track set—a given processing chain, a collection of clips or a group of tracks with their assignments—can be stored and recalled as Track Presets. Cloud collaboration Pro Tools projects can be synchronized to the Avid Cloud and shared with other users on a track-by-track basis. Different users can work on the project simultaneously and upload new tracks or any changes to existing tracks (such as audio and MIDI clips, automation, inserted plug-ins, and mixer status) or changes to the project structure (such as tempo, meter or key).

Field recorder workflows Pro Tools reads embedded metadata in media files to manage multichannel recordings made by in production sound. All stored metadata (such as scene and numbers, tape or sound roll name, or production comments) can be accessed in the Workspace browser.Analogous audio clips are identified by overlapping (LTC) and by one or more user-defined criteria (such as matching file length, file name, or scene and take numbers).

An audio segment can be replaced from matching channels (for example, to replace audio from a with the audio from a ) while maintaining edits and fades in the timeline, or any matching channels can be added to new tracks. Multi-system linking and device synchronization Up to twelve Pro Tools Ultimate systems with dedicated hardware can be linked together over an Ethernet network—for example, in multi-user mixing environments where different mix components (such as dialog, ADR, effects, and music) reside on different systems, or if a larger track count or processing power is needed. Transport, solo and mute are controlled by a single system and with a single control surface. One system can also be designated for video playback to optimize performance. Pro Tools can synchronized to external devices using. Retrieved December 17, 2019. July 25, 2019.

From the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019. ^ Wherry, Mark (April 2012).

Retrieved February 5, 2018. ^ Thornton, Mike (February 2015).

Retrieved December 18, 2019., p. 7, 2. Pro Tools Concepts.

Thornton, Mike (April 2009). Retrieved December 17, 2019., p. 158, 11. Session and Projects.

Retrieved December 17, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019. Sherbourne, Simon (October 18, 2017).

Retrieved December 17, 2019. ^ Wherry, Mark (September 2013). Retrieved February 5, 2018. Payne, John (October 4, 2008).

Archived from on October 4, 2008. Retrieved December 13, 2019. ^. May 30, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2019., p. 38–39. ^. Archived from on June 6, 2015.

Retrieved January 13, 2020. ^, p. 245. Devereux, Brian (May 1986). Electronic & Music Maker: 24 – via. ^. Emulator Archive. February 25, 2009.

Archived from on February 25, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2019. Mellor, David (October 1988).

36: 24–26 – via., p. 387. Lehrman, Paul D. (August 1989).

46: 60–63 – via. Mellor, David (November 1991). 73: 70–74 – via. Brooks, Evan (January 20, 2007). Retrieved June 20, 2015.

^ Goldberg, Michael (December 1994). Retrieved January 7, 2020. Lehrman, Paul D. (November 1990). 61: 60–64 – via. ^, p. 10.

^, p. 389. Retrieved January 12, 2020., p. 216. Sfn error: no target: CITEREFMillner2009. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

Waugh, Ian (November 1993). Music Technology. 85: 56–58 – via www.muzines.co.uk. ^ Thornton, Mike (November 3, 2018). Production Expert. Retrieved December 18, 2019. The Associated Press (October 26, 1994).

Retrieved December 18, 2019. ^, p. 11. ^. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

Boss, Todd D. (March 1994). Retrieved December 13, 2019.

^. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

Retrieved December 13, 2019. ^ Collins, Mike (1998). Archived from on June 7, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2018. ^. Retrieved February 3, 2018. ^ Thornton, Mike (November 3, 2018).

Production Expert. Retrieved December 18, 2019. Daley, Dan (November 1999). Archived from on June 4, 2011., p. 216. ^ Price, Simon (May 2003). Retrieved February 4, 2018.

^ Denten, Michael; Hawkins, Erik (September 2002). Retrieved February 4, 2018. ^. September 15, 2003.

Retrieved January 7, 2020. ^ Thornton, Mike (January 2008). Retrieved February 4, 2018. ^ Price, Simon (July 2004). Retrieved February 4, 2018. ^ Wherry, Mark (January 2006). Retrieved February 4, 2018.

^ Price, Simon (September 2006). Retrieved February 4, 2018. ^ Wherry, Mark (January 2009). Retrieved February 4, 2018.

^. December 1999. Archived from on June 9, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2018. ^ Mark, Wherry (February 2009). Retrieved December 18, 2019. ^ Poyser, Debbie; Johnson, Derek (December 2002).

Retrieved February 5, 2018. Inglis, Sam (June 2006). Retrieved December 18, 2019. ^ Inglis, Sam (June 2005). Retrieved February 5, 2018. ^ Inglis, Sam (January 2011). Retrieved February 4, 2018.

^ Wherry, Mark (April 2012). Retrieved February 5, 2018. Hughes, Russ (September 22, 2014).

Production Expert. Retrieved December 17, 2019. (PDF). Digidesign, Inc. Retrieved October 23, 2013. Wherry, Mark (March 2012).

Retrieved December 18, 2019. ^ Wherry, Mark (January 2016). Retrieved February 6, 2018., p. 187–190, 12. Pro Tools Main Windows., p. 205–213, 12. Pro Tools Main Windows., p. 190, 12.

Pro Tools Main Windows., p. 691, 32. Playlists., p. 1125–1126, 50. Automation., p. 1135–1138, 50.

Automation., p. 947, 43. Clip Gain and Clip Effects., p. 1160, 50.

Automation., p. 16, 2. Pro Tools Concepts., p. 653–664, 30. Editing Clips and Selections., p. 695, 44. Elastic Audio., p. 949–950, 43. Clip Gain and Clip Effects., p. 941, 43.

Clip Gain and Clip Effects., p. 929, 42. AudioSuite Processing., p. 787, 35. MIDI Editors., p. 805, 36. Score Editor., p. 780, 34. MIDI Editing., p. 1355–1357, 60. Working with Video in Pro Tools., p. 188, 12.

Pro Tools Main Windows., p. 1201–1203, 52. Pro Tools Setup for Surround., p. 1057, 48. Basic Mixing., p. 1046, 48. Basic Mixing., p. 1058, 48. Basic Mixing., p. 995–999, 45.

Committing, Freezing, and Bouncing Tracks., p. 1000–1002, 45. Committing, Freezing, and Bouncing Tracks., p. 1188–1190, 51. Mixdown., p. 1381, 60. Working with Video in Pro Tools., p. 19–23, 2. Pro Tools Concepts., p. 420–421, 20. Importing and Exporting Session Data., p. 267–270, 14.

Track Presets., p. 381, 19. Track Collaboration., p. 1333–1336, 59. Working with Field Recorders in Pro Tools., p. 1341–1346, 59. Working with Field Recorders in Pro Tools., p. 1387, 61. Satellite Link., p. 1397, 62.

Pro Tools Video Satellite., p. 1267, 57. Working with Synchronization. Thornton, Mike (July 4, 2018). Production Expert. Retrieved December 12, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

Thornton, Mike (August 9, 2018). Production Expert. Retrieved December 12, 2019., p. 37–40, 5. Pro Tools Systems. Production Expert.

Retrieved December 17, 2019. Thornton, Mike (March 25, 2018). Production Expert.

Retrieved January 28, 2020. ^. Production Expert. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2018. CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown. ^, p. 14., p. 13. ^, p. 15.

^, p. 16. ^, p. 17. Thornton, Mike (July 2005). Retrieved February 4, 2018. Wherry, Mark (August 2006). Retrieved February 5, 2018. September 16, 2004.

Retrieved August 26, 2019. Inglis, Sam (November 2005). Retrieved August 26, 2019. Thornton, Mike (April 2007). Retrieved February 5, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2019. ^.

Retrieved February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019. Retrieved May 12, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

February 19, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020. March 24, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.Bibliography. Collins, Mike (2002). The Evolution of Pro Tools – A Historical Perspective'.

Pro Tools for music production: recording, editing and mixing.:. CS1 maint: ref=harv.

Manning, Peter (2013). Electronic and Computer Music.

The way of the heart solitude. CS1 maint: ref=harv. Milner, Greg (2009). Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story of Recorded Music.

CS1 maint: ref=harv. Battino, David; Richards, Kelli (2005). The Art of Digital Music: 56 Visionary Artists and Insiders Reveal Their Creative Secrets.:. CS1 maint: ref=harv. Avid (2019).

CS1 maint: ref=harv External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to. Avid Pro Tools.